It is an observatory with a twist - a literal twist! Rundetaarn, or the Round Tower, was built in the 17th century in Copenhagen, Denmark. It is the oldest still functioning observatory in Europe.

By the 17th century the science of astronomy was booming, urged on by countries competing to establish the most colonies on foreign soil. The need for accurate navigation to cross vast oceans was now, more than ever, of crucial importance. This cut-throat competition gave rise to the establishment of many national observatories, the first of which was established in 1632 at Leiden in the Dutch Republic. Just five years later in 1637 the foundations were laid for Rundetaarn, at that time known as STELLÆBURGI REGII HAUNIENSIS. And it was completed and ready for use in 1642.

At this time, Denmark was actually a forerunner in the field of astronomy thanks to the work of Tycho Brahe. Christian IV King of Denmark was so impressed with Brahe's contribution to science that when Brahe died in 1601, the King set in motion plans for the observatory in order to continue his research. Of course, the King's plans were not all altruistic; his country was a strong participant in the Colony Battle.

But what about that twist scenario mentioned at the beginning? In a funky feat of engineering the tower was constructed with an internal helical passageway that spiralled up the inside of the tower to its apex, where lurked the observatory itself along with a viewing platform. This spiral walkway is incredibly interesting. If one were to walk up the spiral path along the outer wall of the tower, they would cover 268.5 m, but if one wanted a shorter walk, hugging the central pillar as you ascend shortens the journey to only 85.5 m! Yet ironically, the tower is only 36 m tall. That definitely justifies the term "funky". There was actually a reason behind this incredible design. It was built in this fashion to 'allow a horse and carriage to reach the library, moving books in and out of the library as well as transporting heavy and sensitive instruments to the observatory' (Wikipedia). Below is an image of the walkway.

It is also worth mentioning that this very cool tower has its own library, which houses the entire book collection of Copenhagen university. Apparently the Danish writer H.C. Anderson used the library on a regular basis, and he drew inspiration from the building. Perhaps it was the fantasy-like nature of that spiral walkway that set his creative juices aflowing. These days the library is home to exhibitions of art, history, culture, and science. If I were ever to visit Denmark, I'd be sure to take the time to traverse that spell-binding spiral walkway.

Over time there have been many interesting ascents of the spiral walkway. There have been bicycle races up the tower and bicycle races down the tower. In 1902, a Beaufort car was the first motorised vehicle to ascend the tower. And in 1989, a fellow by the name Thomas Olsen went up and down the tower walkway on a unicycle. The round trip took him just 1 minute and 48.7 seconds, which is still a world record.

***

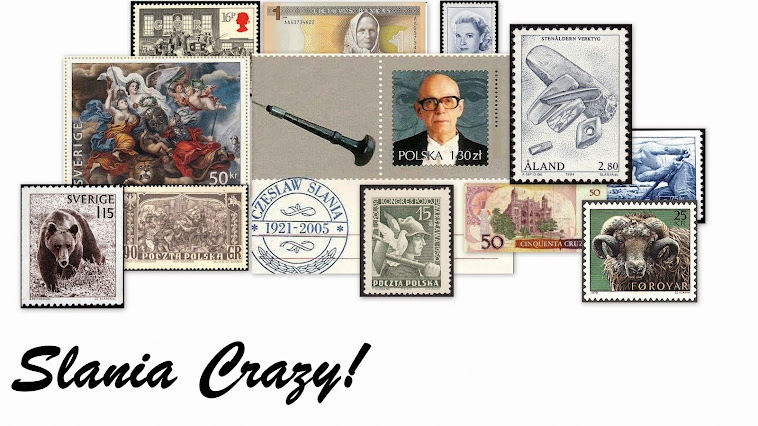

On 12 September 1968 both Denmark and Greenland issued a semi-postal stamp of the same design to help raise money for child welfare programs. For the purposes of this blog I will focus on the Greenland stamp. The stamp issue was designed by J. Rosing and engraved by Czeslaw Slania. This beautiful stamp design, featuring two children wandering the mesmerising spiral walkway, would not look out of place in a children's fantasy novel.

Until next time...